Betye Saar. Faith Ringgold. Mickalene Thomas. Julie Mehretu. Simone Leigh. Jordan Casteel. These are only a few of the Black women artists who have recently exhibited in the nation’s largest museums, like the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim, and the Getty. But long before, it was the Studio Museum in Harlem that had the foresight and intuition to show their work, linking these women both to one another and to generations of Black artists, curators, and critics who have helped reshape American art history over the past 50 years.

Located on Harlem’s famed 125th Street, with Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard on one side and Lenox Avenue on the other, the physical building that houses the Studio Museum has been closed since 2018 due to a $175 million multi-year expansion project. (Part of the collection has been touring nationally in the show “Black Refractions.”) The museum’s new five-story structure, designed by Ghanaian British architect Sir David Adjaye, will more than double its exhibition space. But that space will still represent only a sliver of the Studio Museum’s cultural impact and influence on how people—as well as elite art museums—have come to understand and relate to African diasporic art.

Since its founding in 1968, the Studio Museum has cultivated some of the most lively debates, thrilling exhibitions, and boldest innovators of Black art that our country has ever seen. Before then, Black artists in New York primarily had to rely for exposure on the city’s predominantly white-led museums or the bohemian galleries in Greenwich Village, which largely ignored or marginalized them. “There was so much racism going on at the time. And sexism. It was hard,” says Faith Ringgold, the 90-year-old Harlem-born artist, whose seminal 1967 painting, American People Series #20: Die, a devastating response to the racial violence and bloodshed in the country during that period, now hangs at MoMA. “The struggle was deep.”

In the late 1960s and ’70s, Ringgold organized protests against MoMA, the Whitney, and other institutions for excluding the works of artists of color and women—specifically, Black women. Against that backdrop, Ringgold, who had her first retrospective in New York at the Studio Museum in 1984, knew how important it was for Black artists to have a museum of their own. “It was certainly very exciting, because I was born and raised in Harlem,” she recalled. “It was a big thing for me.” Originally conceived in 1965, at the height of the civil rights movement, the Studio Museum was at first envisioned as an expression of interracial optimism. This was in part due to a coalition of Black and white artists, philanthropists, activists, and educators who had lobbied for the creation of an art space in Harlem to rival the downtown venues—among them Betty Blayton-Taylor, Carter Burden, Frank Donnelly, Charles Inniss, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Campbell Wylly. But the museum was also designed to be connected to the community and operate, at least initially, without curators—only directors—which challenged the elitism and hierarchical structures of the art world. “What our founders were creating was very much a bold experiment around the redefinition of the museum,” said Thelma Golden, the Studio Museum’s director and chief curator, who has overseen its exhibitions and programs since 2000. “This idea of calling the Studio Museum a ‘museum’ was about expanding what a museum is and can be.”

However, by September 1968, when the Studio Museum finally opened in a loft space at 2033 Fifth Avenue, just north of its current location, the mood in the United States in general—and Black America, in particular—had changed drastically. That April, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, and for many, his Dream died with him. The result: Charles Inniss, who became the museum’s first director, found himself at the epicenter of heated debates around African American art at the dawn of the Black Power movement. There’s still no consensus on whether or not a Black guest at the Studio Museum’s first show, Tom Lloyd’s “Electronic Refractions II,” merely hit the protective glass surrounding one of Lloyd’s pieces or destroyed one or two of them entirely. Either way, by most accounts, many actual members of the Harlem community were disappointed by Lloyd’s electronically programmed sculptures composed of colored light bulbs, which recalled traffic lights and theater marquees.

At a moment when the Black Arts Movement, the aesthetic sister to Black Power, was emphasizing figurative art and realistic representations of Black people and their bodies, Lloyd’s show seemed terribly out of sync. For others, though, abstraction was a radical re-envisioning of form and identity, and enabled Black artists to upset the very categories of race that had oppressed them. From its infancy, the Studio Museum enabled these conversations and aesthetic movements to coexist. By the late 1970s, it also became a space where Black women would take the helm, including the three directors who preceded Golden: Mary Schmidt Campbell, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, and Lowery Stokes Sims.

“Our founders, in a very distinct way, did not want to do the narrowing that was done by the mainstream and say, ‘This is what Black art is,’” Golden said. “I think that’s because in the culture we see that we exist in our multitudes.” She continued, “It’s not to say that there weren’t aesthetic arguments and these deeply held beliefs that then were in contest with each other. But the physical space of the museum and then the intellectual space that was bound to that was one that was wide and had room for all of it.”

In 2001, Leslie Hewitt attended the first of the museum’s signature “F-Show” exhibitions, “Freestyle,” which was curated by Golden and is now legendary. The show not only debuted the work of then emerging artists such as Sanford Biggers, Mark Bradford, Rashid Johnson, and Julie Mehretu, it also introduced the notion of “post-Black” art, a concept that actively rejected the idea that there is one way of looking at Blackness. “Freestyle” and that era were transformative for Hewitt’s practice, which blends sculpture and photography. “The ‘Freestyle’ show had so many different forms and arguments that the artists were making in their work. It was just so varied,” she said. “Within the structure of an institution like a museum to not see a monolith [of Black life] presented but an active decentering of what that means was exciting for me to see as an artist.”

In 2007, Hewitt was accepted into the Studio Museum’s renowned artist-in-residence program, a coveted 11-month residency for early-career Black and Afro-Latinx artists. The program’s alumni list includes David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, Adam Pendleton, Kehinde Wiley, and many of the women artists featured here, making it an institution all its own. Hewitt remembered looking out the window of her studio onto 125th Street and feeding off the energy. “You can’t help but think of Roy DeCarava,” she said, recalling the photographer whose images of artists and musicians captured the spirit of Harlem in the 1940s and 1950s.

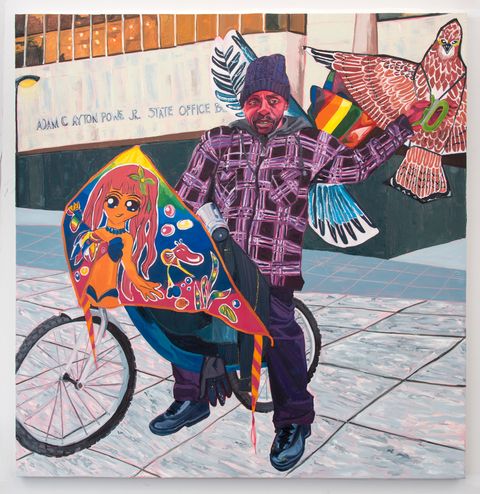

Painter Jordan Casteel, who began her own residency at the Studio Museum in 2015, knew she wanted to join the program after finding out that artists like Wiley and Mickalene Thomas had been through it. What Casteel did not know was how much being in Harlem would influence her work. In graduate school, Casteel painted wall-size nudes of Black men with whom she was friends, but in her residency, she began to document the street vendors, restaurant owners, and residents whose lives animated the neighborhood. “The first time I went outside with a camera, it was not the easiest thing for me. I had to get over my own introversion to introduce myself to people,” Casteel said. “My understanding of how I relate to the world shifted in that moment. I realized and needed to become accessible to the community, and I needed that kind of reciprocation.”

This past summer, as the Covid-19 pandemic disproportionately affected Harlem, and Black Lives Matter petitions and protests decried racism at leading cultural institutions, the Studio Museum’s place as a home for Black artists, who have always been a catalyst for real justice and true racial equality in the U.S., became all the more crucial. “I think many Black and BIPOC-led institutions see this as a moment to further the understanding of our roles in our cultural communities,” Golden said. “The Studio Museum was founded in a moment just like this, and I imagine there are organizations being founded right this moment in relation to what this recent history has brought to the cultural world.”

“If there’s a secret sauce, it’s Black,” said Naudline Pierre, a Haitian American painter who finished her residency at the Studio Museum last year. “It means that I can skip a layer of explaining my experience,” Pierre said. “I can walk into a room and feel like I belong.”

— THE ARTISTS —

Text by Harper's BAZAAR Staff

·

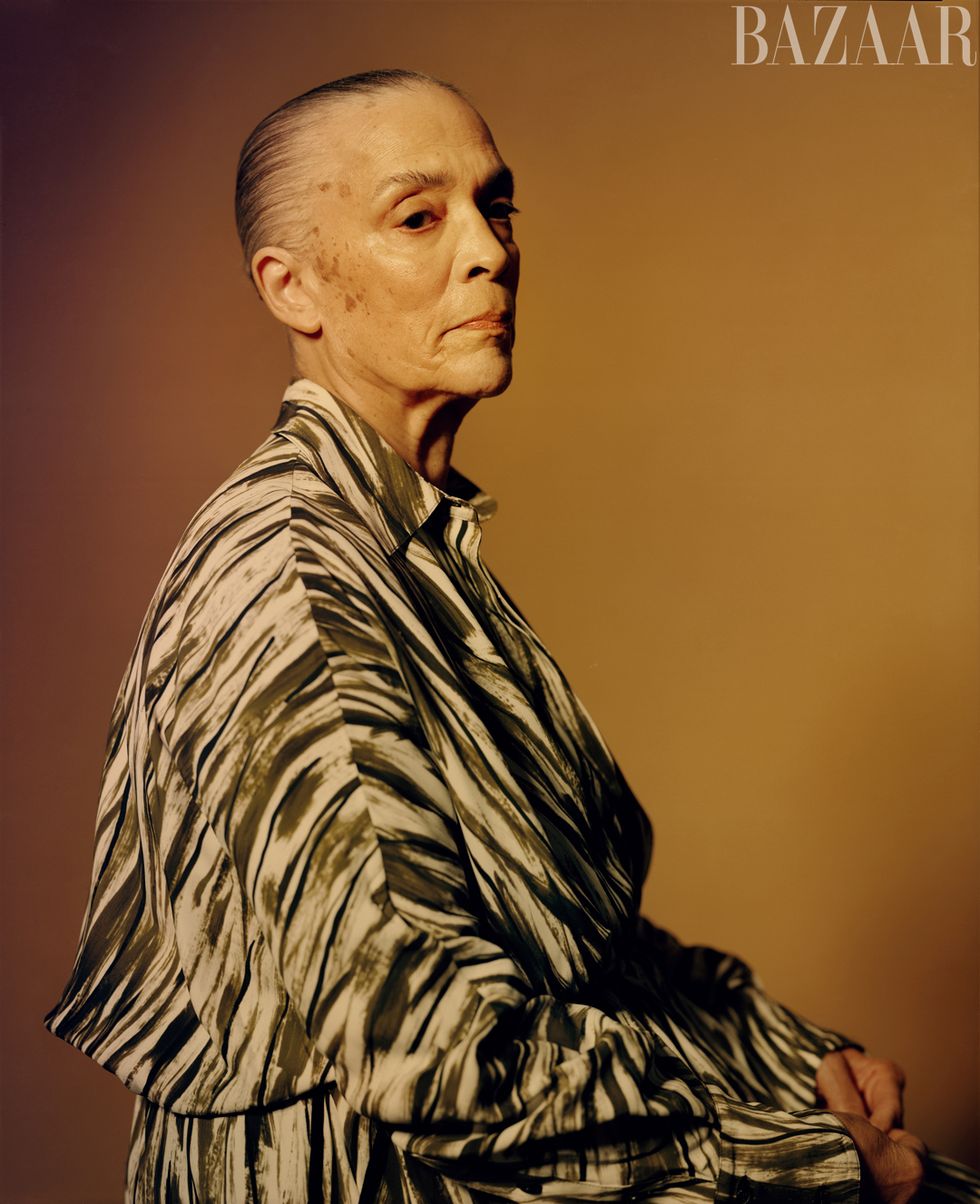

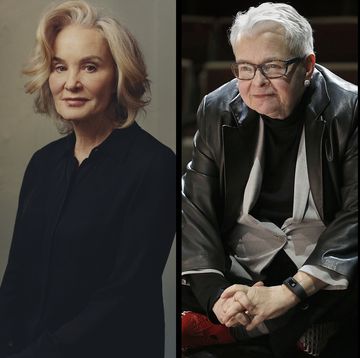

Faith Ringgold

Faith Ringgold had her first major museum retrospective in New York at the Studio Museum in 1984. She was 54 at the time. When she first started making work in the 1960s, the art world was not rife with opportunities for Black artists—and even less rife with them for Black women artists.

But Ringgold, now 90, says she came of age in Harlem in an era when any notion that she might be accepted in that rarified cultural domain would have been considered outlandish. “If you were a woman, you expected to be left out of the art world,” she explains. “I was living right there in the neighborhood with all these famous Black artists—Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence. But they were all men. … They were always men.”

Being sidelined, though, only seemed to strengthen Ringgold’s resolve. She made art that was overtly and provocatively political, and unflinchingly addressed the stark realities of the civil rights struggle, crafting paintings, quilts, and soft sculptures that were pointed, graphic, and incendiary in a way that sometimes belied their form. She also risked her own safety and freedom in the 1960s and 1970s to protest institutions that excluded women and artists of color—MoMA, The Met, and The Whitney among them. “How dare I come along, a Black woman, and be political? So now I’m going to have trouble with that. And so I figured, well, hell, since I’m having trouble any, why don’t I just do what I want?” she says. “So I’m going to do what I feel at the time. I’m going to portray the history of the times we’re living in. And if they leave me out, they just have to leave me out.”

Ringgold’s works are now in the permanent collections of some of the world’s biggest institutions—including MoMA, The Met, and The Whitney.

·

Jordan Casteel

“I had a list,” says painter Jordan Casteel. “Mickalene Thomas was on it, so was Kehinde Wiley. I was like, ‘These are careers that I respect. What are the common denominators between all of them?’ The Studio Museum was the common denominator for 99.9 percent of the artists that I admired.”

Casteel, who creates large-scale portraits from her own photographs, grew up in Colorado, but came to New York shortly before doing her residency at the Studio Museum in 2015 and 2016. She says that discovering that Thomas, Wiley, and so many other artists whose work and perspectives she valued had been through the museum’s artist-in-residence program inspired her to want to apply—even before she completed her MFA in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale School of Art in 2014.

Working and living in Harlem would have a profound impact on Casteel’s practice, but also on her on a personal level, as she developed deep connections to both the museum and the community that surrounded it. She also very quickly recognized why so many artists maintained strong links to the Studio Museum for years beyond their residencies. “I knew that there was something magical about a place that had allowed all of them to find real creative clarity and possibility,” she says.

·

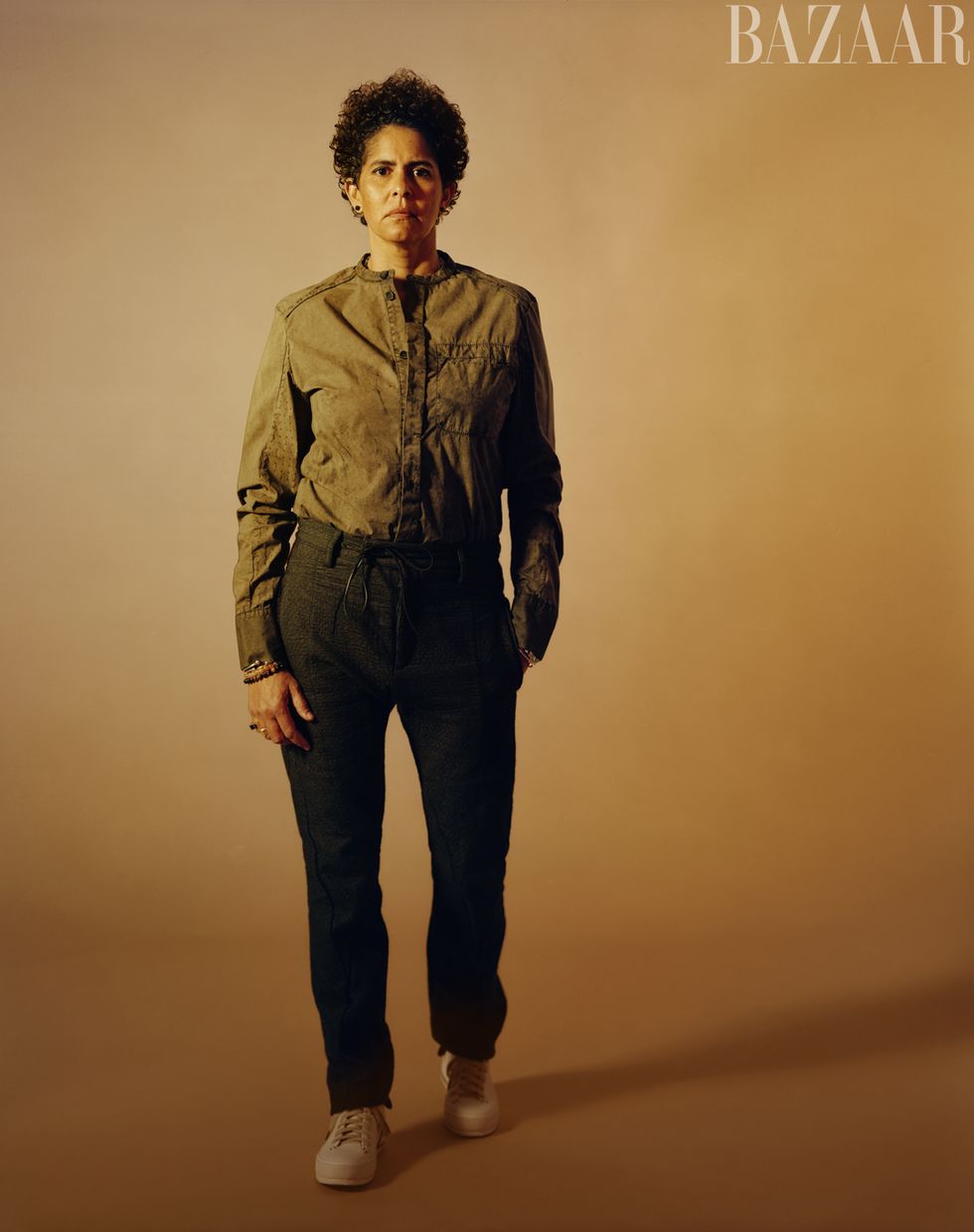

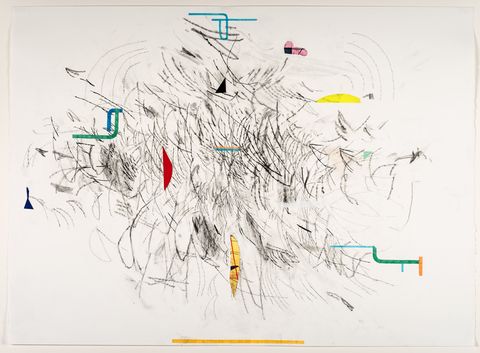

Julie Mehretu

“Harlem became really important to me and to the fabric of my life here, and it became this neighborhood that we wanted to make a different kind of a commitment to,” says Julie Mehretu, whose sweeping, dynamic, abstract paintings and compositions will be on display as part of a mid-career survey at The Whitney in March—including a selection of new work completed during the pandemic.

Mehretu did her residency at the Studio Museum in 2000 and 2001, at a time when both Harlem and the art world were changing. The Internet and globalism were booming, and a massive (and controversial) commercial renovation had overtaken 125th Street, bringing in Disney, Starbucks, and a Magic Johnson multiplex. Bill Clinton would soon follow, opening his post-presidential office there. At the same time, a more pluralistic, multifaceted view of the African diaspora and the art being made by Black artists—punctuated by the Studio Museum’s now-seminal “Freestyle” show, of which Mehretu was a part—ushered in a new wave of talent and perspectives. “I really went to the studio almost every day. I was there working as much as I could, and so there was this intense sense of community that developed from that, and we would go to the Lenox Lounge or wherever to have food or drinks afterwards,” says Mehretu. “There was this energy that existed around all of that, this kind of emergent possibility that was taking place as not just an alternative to what was happening in the art world and in the conversation of the art world, but as something that could participate in shifting that conversation holistically.”

The attacks of 9/11 would also have a profound impact on the Studio Museum community, claiming the life of Michael Richards, a former artist in residence who was working in a studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One of the World Trade Center that morning. “His service was held at the Studio Museum, and I remember that being a big scar or marker on the entire community up here,” Mehretu recalls. After 9/11, Mehretu says, the more conservative tenor in the United States, where much of the perceived progress of the 1990s became stifled, also proved formative. “It put a halt to any kind of global positivism,” she says. “You had this kind of reactionary shift that took place, and I think we’ve been negotiating that since.”

Mehretu has continued to live in Harlem. “Really, it became kind of a core part of the way that I think and make,” she says. “Maintaining a language in abstraction, continuing to work in abstraction, and choosing that … I think of it as a super-potent political language. And what I mean by that is political as a way to find freedom, to mine possibility and invent, and the creative and radical imagination that could only exist with an abstraction, because there are some things that words can’t necessarily articulate.”

·

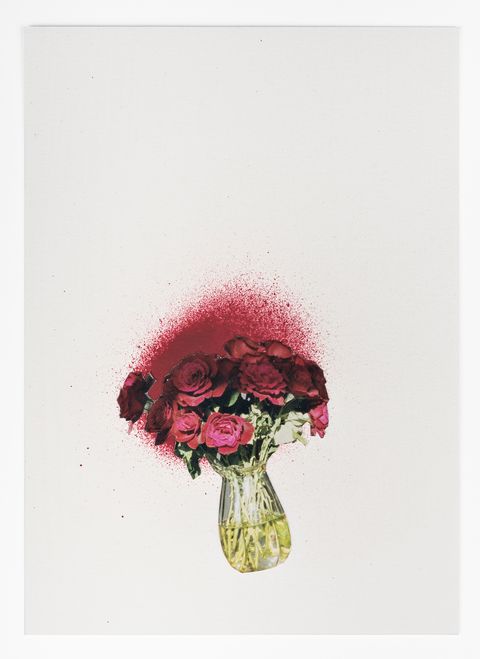

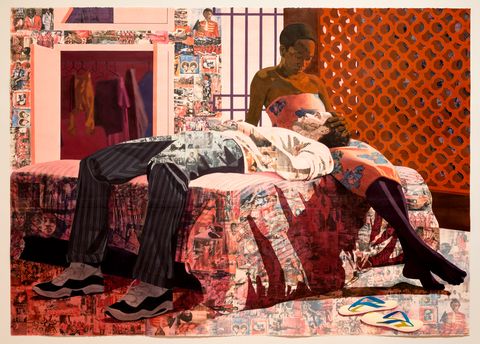

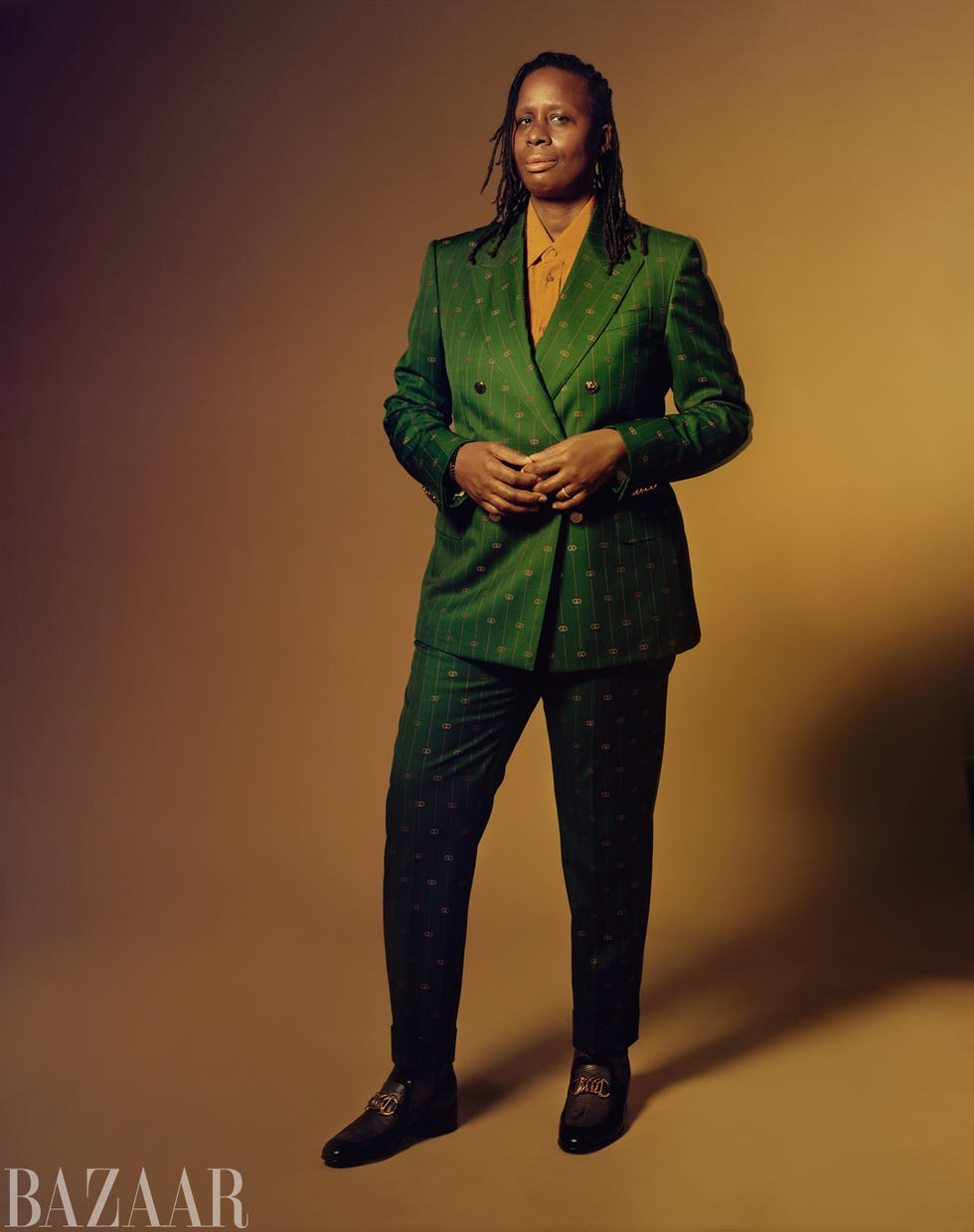

Mickalene Thomas

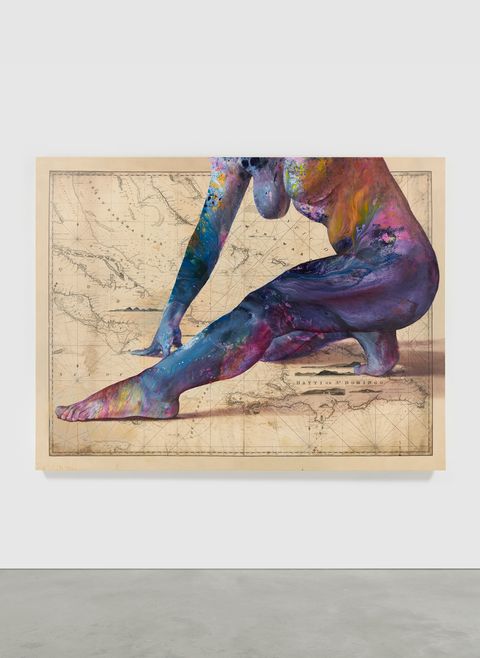

Mickalene Thomas’s mixed-media paintings and images of Black women have graced the walls of some of the world’s most vaunted galleries and museums. But for Thomas, the process of getting there was neither easy nor immediate.

After completing her residency at the Studio Museum in 2003, Thomas toiled away in her Brooklyn studio, cash-strapped, gallery-less, and running up against a litany of challenges. “Many of the artists [in the residency program] went on to pursue galleries and had big shows. Even though I was in a lot of collections, I actually struggled,” Thomas recalls. “I rented a studio in Dumbo and encountered obstacles with getting exposure and paying the rent. But at that time, those circumstances were also what made it exciting. It’s why I continue to work so hard to this day, to be quite honest.”

The root of the problem, Thomas says, was her choice of subject matter: She was told over and over that the audience at many galleries and institutions wasn’t “ready” for her work. “My work has been censored for being ‘explicit.’ Our society is still not quite ready to see images of two Black women loving each other. I think in this country, we are still very resistant to seeing the beauty of Black bodies embracing,” she says. “Because I make images of Black women, there were constant barriers. Quite frankly, many institutions were not ready to celebrate Black women. Thankfully, some doors have opened. But I will continue to make the work because I know it inspires people and creates an impact. These setbacks only fuel my desire to persevere. My work is powerful so it’s going to ruffle many feathers.”

Thomas remembers a moment when her 2012 exhibition “Origin of the Universe” was on view at the Brooklyn Museum, and she saw an older woman smiling ecstatically in front of her painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe: les trois femmes noires. Not wanting to interrupt the woman, Thomas was reluctant to introduce herself. But when someone told the woman that Thomas was the artist, the woman burst into tears and thanked her profusely. “That is why I make and do what I do, for those women who can see themselves in my work and have a sense of validation, that there’s a celebration of Black joy and Black love and Black leisure,” Thomas says. “It’s these moments that inspire me to continue creating.”

·

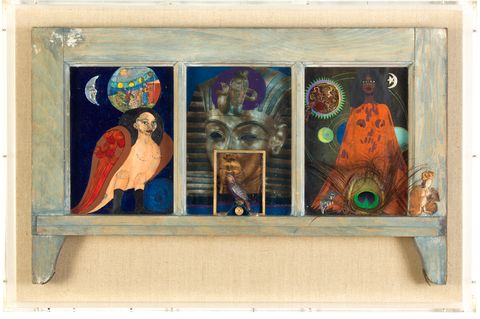

Ming Smith

Since the late 1960s, Ming Smith has explored themes such as race, gender, and beauty in her photographs, performance portraits, and pictures of cultural figures like Nina Simone and Tina Turner. But Smith’s work has also always powerfully captured what’s unseen, and the social, emotional, and psychological narratives that hover behind images and beneath surfaces.

In the 1960s, Smith became affiliated with Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of Black photographers formed with the goal of documenting and expanding the dialogue around Black culture. When the group was the subject of a Studio Museum show in 1972, Smith was the lone female member. But seeing her work in that context at that time resonated with her deeply. “Showing at the Studio Museum is different, because it was one of the institutions you could always see and experience Black art,” she says.

What interested Smith was that the museum didn’t limit the art that was shown to any one perspective or element of the Black experience, but instead seemed to view it as something living, breathing, and forever evolving. It was an approach that always left room for new voices and ideas to enter the conversation, which she thinks is an important part of the Studio Museum’s legacy.

“When I think of ancient Egypt handing knowledge to the Greeks and the Greeks influencing the Romans, and the Romans influencing the British, and the American Black musicians influencing rock and roll, blues and jazz, my work was and continues to be heavily influenced by the music and art I absorb,” she says. “Legacy, to me, in terms of art, means to be influenced and to influence. Legacy is a gift.”

·

Firelei Báez

“Legacy for me means how you, how your actions, have affected the world around you, and what you’re leaving behind for someone to take and move forward with,” says Firelei Báez, whose paintings, murals, works on paper and canvas, and installations have explored the interrelationships between art, race, gender, history, and power.

Báez, who was born in the Dominican Republic, says that studying and later working in New York offered her invaluable exposure to the art world, but also an understanding of how to negotiate it on her own terms. “I was lucky enough from my upbringing to consider closed doors as just a query into navigating the world differently,” says Báez. “It has allowed me to engage with a broader audience and still honor all those beautiful nuanced parts of my Caribbean self, my Black self, my American self, my Latin American self in ways that I would not have been able to otherwise,” she explains. “For me, it has been a matter of fully centering where I came from—the Caribbean, specifically Dominican Republic and Haiti—and recontextualizing it within a global context and having others really enjoy and revel in the concrete facts of my lived experience.”

·

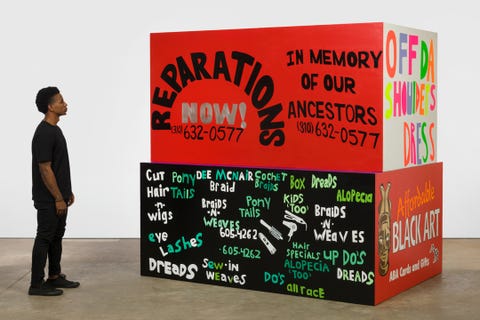

Abigail DeVille

For Abigail DeVille, whose sculptures and installations frequently engage with the history of marginalized people and places, the Studio Museum’s role as an institution aligned with that mission is what drove her to want to become an artist in residence.

“There is a multiverse of legacies that define our current condition institutions, perceptions, and how we can accurately see each other and ourselves. In each project, I mindfully navigate the systems that function in this American experiment—thinking about the framework the Founding Fathers set up and how that defines our vision and perception of freedom,” says DeVille, who completed her residency in 2013 and 2014. “My family is a part of the great migration arriving in Harlem in the 1930s and ’40s from Richmond, Virginia, and the Dominican Republic in the early 1960s. I wanted to be in the middle of this Black diasporic mecca. That felt vitally important, connecting me to my ancestors and the shared migrant immigrant experience that defines our American lives,” she explains. “I believe the legacies that have been left for us by our ancestors are calls for freedom from the margins of society. From the beginning of Western history on this continent, there have been parallel stories of freedom struggle. It is that struggle and the stories regulated to darkness that I hope to illuminate.”

·

Maren Hassinger

L.A. native Maren Hassinger, a Studio Museum artist-in-residence in the mid-1980s, saw the program as a chance to live and work in New York, which at the time was in the throes of a creative art boom fueled by superstar artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, and Julian Schnabel.

“I was living in my studio on San Vicente Boulevard with my husband, Peter, who was a writer, and I wanted the opportunity to come to New York,” Hassinger recalls. “That was the motivation for applying, because it gave me a stipend so I could live in New York—plus the job of actually having a studio that I could go to every day. So I left Peter and I left Los Angeles and moved to New York.”

For Hassinger, the go-go, larger-than-life energy of the’80s art world occasionally proved inescapable—even in her own studio. “One day, without any to-do or anything, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat showed up along with Andy’s bodyguard, who was very slight and appeared to have no weapons—I mean, he was much slighter than I was, and I’m five foot three,” Hassinger recalls. “Basquiat seemed to like some drawings on the wall of my studio mate, Candida Alvarez, but they were actually the drawings of a child she knew. They weren’t actually her work. … And Basquiat was kind of turning around and dancing and exclaiming about these drawings. And then Andy was sitting next to me, and I was making these collages out of preserved leaves that I had found. He said they were quite beautiful. I do not remember what they said to Charles Burwell, who was a painter and the other person in the studio,” she says. “I don’t know whether he was there or not. I think he was there. But it was so shocking that maybe he just couldn’t say anything.”

After completing her residency, Hassinger set out to find a gallery. Instead, she took a teaching job in Baltimore. It would be more than 25 years before she got one, the Susan Inglett Gallery in Chelsea. “After my kids were born, I moved out of the city for 20 years,” she says. “As much as I liked teaching, which I liked very much, I really always held it in my head that one day, I would have a gallery in New York and a studio in New York, and I would see some prosperity in that. And that is exactly what happened. But it did not happen until I retired from teaching and moved back to New York.”

To Hassinger, an artistic legacy isn’t built around just the work you make or show, but everything you do. “For those 20 years that I had all the students, there were certain ideas that I wanted to instill. And I think that many of the students who have gone on to be practicing artists have kept those things in mind. And they have to do with never stopping—to just keep working. And trying as much as you can to talk about how you feel in relationship to the world, and figuring out a way to represent that,” she says. “I’d like to say that we are all related,” she muses. “I truly believe that. And I believe that if we all lived lives in which all of us believed that, the world would be a better place.”

·

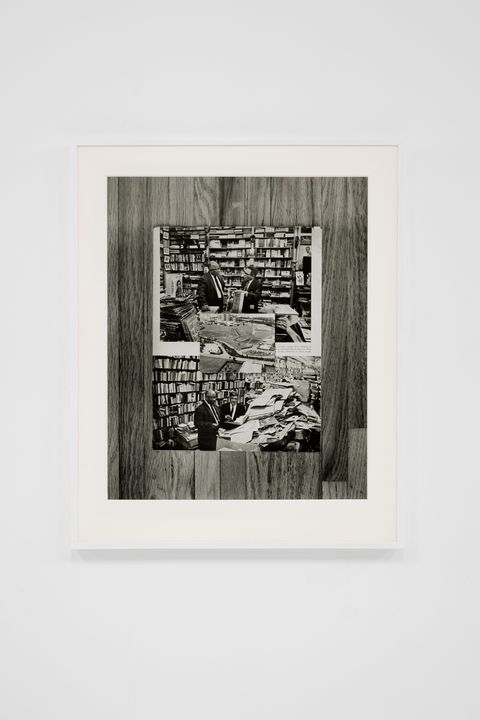

Leslie Hewitt

Leslie Hewitt’s work willfully defies easy categorization, incorporating both found and fabricated items, historical documents, and elements of sculpture and photography.

To Hewitt, a 2007–08 artist in residence, the museum’s openness to new forms, narratives, and modes of expression—and its support of art that deals in a multitude of themes, identities, and experiences—has been key to its vitality. “It pretty much validates that the future is what you project it to be,” Hewitt says. “Even though we could say the Studio Museum supports Black art, even in saying that, it actively problematized what that looks like. For me, for my New York sensibility, whatever that means, it was like, ‘Yeah, be original.’ What does that look like? It looks as distinct and interesting and particular as who you are or the experiences that you collect and culminate into whatever it is your form is,” she explains. “Legacy is navigation. It is an unbroken and focused promise with the past, present, and future. It offers a foundation for innovation and expansiveness at best, and struggle and trepidation on the other side of that, providing an interesting internal battle or process of autopoiesis.”

·

E. Jane

“Who has gone before you that inspires you to keep going? Who makes you feel like you can do what you’re doing? Who do you want to be in conversation with? I think legacy is about conversation,” says E. Jane, a 2019–2020 artist in residence whose work interrogates aspects of race, gender, and identity in popular culture and digital and social media.

E. Jane, excerpt from LetMEbeaWomanTM.mp4, 2020. Single-channel digital video (color, sound), fabric, monitor, 06:56 min. Courtesy the artist.

“I definitely think just getting into the program encouraged me,” Jane says. “Working with the Internet, technology, performance, and engaging Black femme performance forms, thinking about R&B music and the history of the Black American diva—these hyper-femme and Black concepts don’t always feel like they have space in the art world. I feel l like the residency really told me, ‘There is space for your work in the art world.’”

Jane says entering the institutional realm of galleries and museums has been eye-opening in other ways. “I think because the performance work I do is very deep performance, sometimes it’s really confusing. It’s like, I’m an artist, but I also have a music project through an alter ego, MHYSA. She actually performs in the world. I think sometimes people have a hard time understanding, like, ‘How is this art?’” Jane explains. “In general, I think I work with a lot of new forms. I definitely see myself as a futurist, and the new is scary.”

·

Steffani Jemison

Steffani Jemison’s conceptual pieces mine personal narratives, codes, language, an array of visual forms, and even literature. Jemison, a 2012–13 artist in residence, says that for her, the Studio Museum’s true center of gravity is the sense of community it fosters—and not just among contemporaries.

“One of the first exhibitions that made a really strong impression for me was an exhibition of work by Glenn Ligon in the early 2000s,” Jemison recalls. “It was a series of paintings he made that were in conversation with the James Baldwin essay ‘Stranger in the Village.’ I still remember entering the museum and seeing this one painting in particular, just massive in scale, and encountering the language from his essay, which was very intimate and familiar to me, and recognizing this chain of connections, this chain of kinship, from Baldwin to Ligon to myself, as a young student realizing that this could be me, actually—that I, too, could participate in these conversations.

“As a younger person, the idea of legacy always seemed really abstract. Legacy described the way that torches get passed from one generation to the next, super formal. Legacy was a very distant concept. And what I learned from the Studio Museum is that legacies are built. They’re built with intention. That legacy is rooted in very real relationships between real people. In fact, another word for legacy might actually just be community. And the Studio Museum is so good at building and uplifting and then circling and supporting the communities that it protects,” Jemison says. “It’s a tricky tightrope, to build a space that is by us, for us, but also open to everyone—a space that prioritizes the ideas, challenges, problems, questions, concerns, community, shared references, and reality of Black lives. But the Studio Museum makes it possible for a student like me to imagine myself as part of a chain of writers, thinkers, and artists who were all committed to the same questions. We’re all trying to work out the same stuff.”

·

Naudline Pierre

“The idea of legacy in my own work brings up an understanding that this work will most likely be around long after I’m not. It pushes me to ask myself, what is it that I want to say to those in the future? It’s like leaving a note that says, ‘I was here,’” says painter Naudline Pierre.

Pierre began her residency in 2019, not long after the Studio Museum building closed for renovations, and completed it last year, amid the pandemic. But she found the physical distance from her fellow residents and the museum’s curatorial staff did little to inhibit the connections they all formed. “I think institutions and galleries can provide a certain type of validation, but it should ultimately be about protecting and fostering growth in one’s work. That’s something that has to start in the studio first, then it’s about finding places that are aligned and want to do that with you. During my time at the museum, I felt really seen and like I had the resources to grow,” Pierre says. “There’s a long history of artists that have gone through the program, and I knew that I wanted to do the same. I was drawn to the residency, because I wanted to be part of that lineage, part of that conversation. It was and continues to be important to me to find spaces where I feel that I’m reflected.”

·

Xaviera Simmons

“For me, what really stands out is people that I’ve interacted with on and off since I started going to the Studio Museum in the early ’90s,” says 2011–12 artist in residence Xaviera Simmons. “I think a lot about Lowery Stokes Sims and about Thelma Golden, and how much work has been done to keep the museum on the cutting edge of culture.”

Simmons, whose practice encompasses performance, photography, video, painting, sculpture, and installation work, says that her time in the residency program made her feel not like she was operating in the shadow of a great legacy but helping to write the next chapter of one that she already had a place in. “It has formed so much of my thinking around art making, and art practices, and art community. I think a lot about being a descendant of slavery, and what that means, and what responsibility I have, not only to the history, and to the present, but to the future. The artists that have gone through the Studio Museum—we communicate, we’re in conversation, we’re supportive of each other. And that means a lot to me. I’m so excited for the Studio Museum to reopen, reinvigorated, and with an even more firm commitment to narrating the country’s legacy and history.”

·

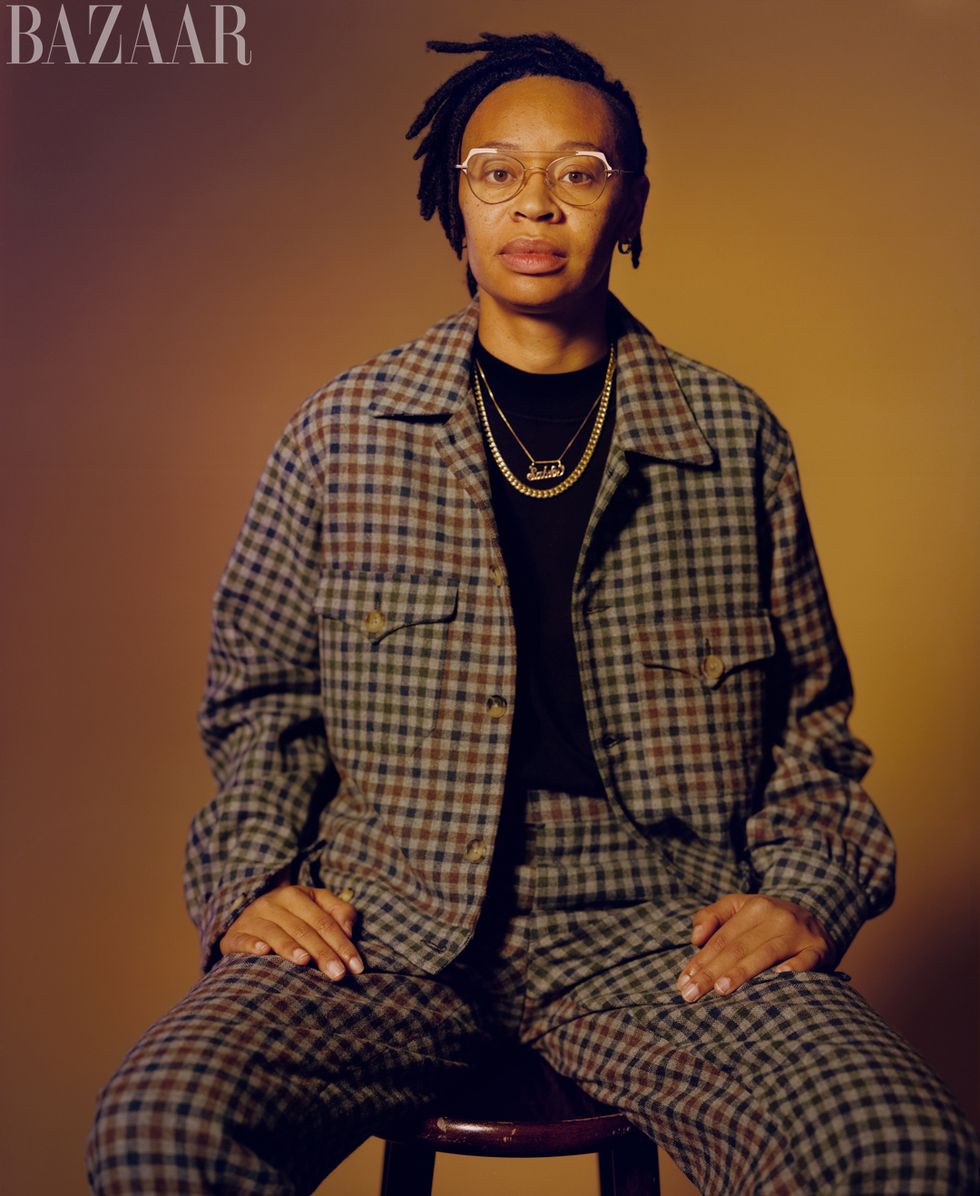

Sable Elyse Smith

Before she was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum, Sable Elyse Smith worked in the museum’s education department, which Smith says has informed the way she views the role of institutions in the art ecosystem.

“I think entering institutions specifically—as an employee, as a visitor, as an exhibiting artist, as a collection artist, as a trustee, as a friend of the institution—I think this accumulation of experiences and identities has had one of the greatest impacts on me. It was here that I actually began to understand where power lies, where and how something could be altered, changed, expanded,” Smith explains. “As an artist, this knowledge gave me more agency to decide how and on what terms I want to operate within the art world and where I may have the ability to impact or change something.”

But on a more fundamental level, Smith says that working in a museum gave her an understanding of why they are so vital. “Something that I have learned along the way and which always surprises and amazes me is the impact that the work has on people,” she says. “People outside of the art world, people who just love art, people who stumble into the museum that day, people on class trips. The work just sits there in public waiting for a person to encounter it. And every single time I witness one of those encounters or someone reaches out to me is really rewarding. It places things in a different perspective. And realizing that the work potentially has the power to outlive me and that those encounters may continue for generations to come is awe inspiring. But it also makes what it is I want to say, what it is that I contribute, that much more important to me.”

·

Saya Woolfalk

When Saya Woolfalk was admitted to the artist-in-residence program in 2007, she was coming off a two-year period of living in Brazil, where she studied folkloric performance traditions. “I was encouraged to apply by mentor, Candida Alvarez, who is a painter based in Chicago,” Woolfalk says. “I applied three times, and when I finally got in, I was elated. I needed a community. I needed a group of people—like-minded people—who could help me parse through this information I’d collected over the course of two years.”

Woolfalk says that she felt at home right away. “I almost immediately began to invite people to my studio. I invited people to my studio to do studio visits. And one of the first people that I invited was Dr. Lowery Stokes Sims, and she accepted,” Woolfalk remembers. “It was ridiculous. This titan of the art world was coming to my studio, which I had painted. I painted the ceilings. I painted the walls. I carpeted the floor. I had turned it into a multimedia installation and stage set. And she and I just had a conversation. We sat together. I was sitting on the floor, and she was sitting in a chair, and we talked. She told me about other artists. She talked to me about history. And for me, that was a threshold moment, a gateway moment—a moment that turned something that had always been a fantasy into something that was a reality. I had entered the art world.”

Hair: Eric Williams for Shea Moisture and Tashana Miles at The Chair Beauty Loft for The Chair Beauty; Makeup: Katie Mellinger for Pat McGrath Labs; Production: Peter M. Murray and Eric Jacobson for Hen’s Tooth Productions.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE OF BAZAAR