The journey to bring Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler’s portrait to “The Schuyler Sisters and Their Circle” exhibition at the Albany Institute of History & Art began in Spring 2018. Implementing an exhibition like “The Schuyler Sisters” is like planning and weaving a coordinated complex web with a little detective work mixed in. Curator Diane Shewchuk worked for eighteen months to develop the exhibition. This included negotiating loans from other institutions, some taking over a year to secure and organize shipment or pick-up.

Portrait of Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, on loan from the New-York Historical Society, on display at the Albany Institute of History & Art

Tangential Storytelling

The Schuyler sisters’ portraits are the heart of the exhibition that provides tangible evidence of their lives. To help tell their stories, over 200 items were used in this exhibition a majority from the Albany Institute of History and Art's own collection and objects borrowed from 24 lending institutions. The texts included in the exhibition also tells their story that a visitor would miss large parts of the narrative if they skipped reading. “We know about the family through the paper trail they left behind,” said Shewchuk. “We wanted to feature texts that make these historical figures real and place them in the context of real human lives.” Documents loaned include correspondence between the Schuyler sister’s father General Philip Schuyler and his grandson in which his grandson asked the General questions about his life. Shewchuk chose to exhibit the page where General Schuyler wrote that his favorite game was backgammon. It’s why you’ll find an 18th-century backgammon table in this exhibition. Another document is a recipe book where Shewchuk features the page with a recipe to relieve teething pain in children and a remedy for horses. “It is tangible evidence that illustrates General Schuyler’s life beyond being a general to include his concern as a father and his passion as an avid horseman,” said Shewchuk. Another letter mentions General Schuyler bringing his grandchildren objects made with birch bark and embroidered moose hair. Next to this letter, you can see examples of this Native American art form. “This exhibition is very tangential...we use objects to tell stories, so when creating this exhibition I’ve thought about what objects can we use as well as the stories they told and how they would look in our galleries.

“The Schuyler Sisters and Their Circle” at the Albany Institute of History & Art

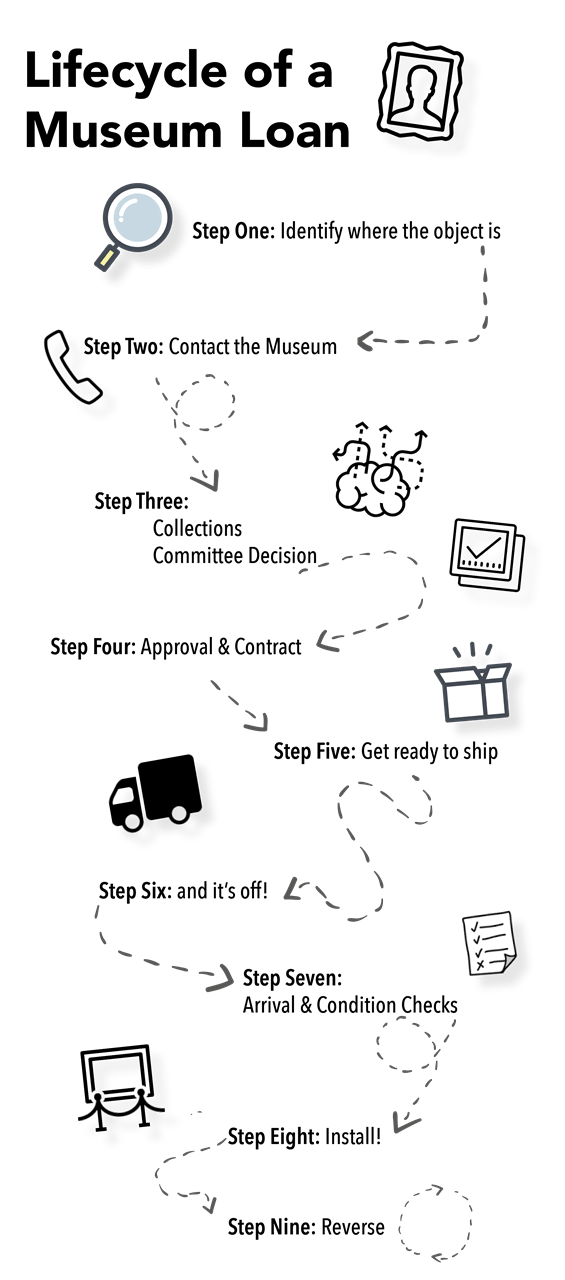

The Lifecycle of a Museum Loan

The Albany Institute borrowed collections from 24 lending institutions for “The Schuyler Sisters and Their Circle” exhibition. While there is a standard order of procedure for most loan agreements, each lending institution has its own timeline and specifications that accompany loaned items.

Step One: Identify where the object is

Curators use different resources from online collections portals, records from previously loaned items, or connections with colleagues to find objects that they are interested in including in an exhibition. Shewchuk relied on her expertise in the field and her contacts from across the state to help discover where objects were held. Visiting and keeping up to date on exhibitions in a curator’s specialty also helps to identify where certain objects are housed. Items that are in museums are easier to find, but others, like Angelica Schuyler’s portrait, that are in private collections require more detective work.

Curator as Detective

To discover where Angelica Schuyler’s portrait was, Shewchuk had to find the current owner. “I knew who had it years ago but then I had to track down the current owner using obituaries...and I just kept going. I wrote to the current family who owned the painting to see if the portrait could come to Albany. Finding objects comes from following one clue to another clue and that’s how an exhibition can come together, while at the same time keeping in mind the story you want to tell and how these objects fit… Sometimes you really get into the weeds to find things..one thing can be connected to another.”

Step Two: Contact the museum

Once a curator has located the object, they contact its home institution regarding availability. “Are there exhibition plans in place?” or “Is this item going to be traveling?”

If the object is available for loan, a letter is sent from the Director of the Borrowing Institution to the Director of the Lending Institution requesting the loan. This letter outlines the details of the exhibition timeframe and will include a facilities report from the borrowing institution.

Step Three: Collections Committee Decision

The lending institution will decide if the object is in good condition. Depending on the type of material, once an object has been on exhibit it must “rest” in a controlled environment before it can be shown again.

Once the Collections Committee approves of the loan request, they make a recommendation to the museums’ Executive Committee to approve the loan and then present the loan request to the full board. This entire process can take several months and some institutions have a long lead time for any loan requests. For example, Catherine Schuyler’s portrait needed to be requested a year before the exhibition began because of the New-York Historical Society’s requirement. “That is why it is important to build the exhibition timeline around the larger loans so that these objects are secure in order to build the show,” said Shewchuk.

Step Four: Loan Agreement

Once the loan is approved, the lending institution creates a legal contract with the borrowing institution called a loan agreement that specifies any specific requirements for the item.

Loan Negotiation

For each lending institution, Shewchuk had to negotiate the loan requests, arrange proper documentation, arrange transportation, and organize transportation logistics for staff from the loan institutions who needed to accompany their items to oversee unpacking, installation, and perform condition checks.

For smaller institutions who loan collection objects or for institutions that are in close proximity to the borrowing institutions, not all of these logistics are necessary. Items that Fort Ticonderoga loaned did not need a special truck but were transported by their staff to the Institute. The same is true for timelines of requesting loan items. Shewchuk secured all of her New York City loans first and from there, was able to tighten the exhibition schedule and approach smaller institutions.

Most lending institutions, especially the larger organizations, will have a loan fee, a conservation fee, a fee to bring the object from its warehouse/collections storage to the museum for pick up, and a packing fee. Costs vary based on the type of object (i.e. special care and conservation), the distance the object will travel and larger institutions may request a higher loan fee.

Step Five: Get Ready to Ship

The lending institution will also perform a condition check and create the specifications for the shipping crate, usually measured specifically for the object. The design of the crate and shipping is arranged by and paid for the borrowing institution.

For this exhibition, Catharine Schuyler’s portrait had to have a custom crate for its rococo frame and well as glass installed over her portrait for protection.

Step Six: and it’s off!

The Albany Institute of History & Art needed to buy the exclusive use of a truck to collect the NYC loans. The truck made stops at the New-York Historical Society, Museum of the City of New York, Columbia University, Gilder Lehrman Collection, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met has a special requirement to be the last stop and the first to have items unloaded at the Institute. Additionally, a courier from The Met accompanied the delivery to the Institute.

Step Seven: Arrival and Condition Checks

Upon arrival, Shewchuk took photographs of the crates and sent images to each lending institution. She also informed the lending institutions where these items would be located in storage and their security level until it was time to remove them from their crates for installation. Most loaned items need 24 hours to acclimate to the new environment before they could be opened. Condition checks are also done throughout the exhibition.

Step Eight: Installation

Either lending institution staff or the curatorial staff from the exhibiting museum will remove items from their crates and begin the installation process.

Step Nine: Reverse

When the exhibition finishes, the process reverses as the collections team pack each item and sends it back to their home institution. Packing materials are saved and labeled so that items can be packed how they arrived. Another condition check is done by the borrowing institution and then again by the lending institution when it arrives back.

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask About Borrowing

When it comes to approaching other institutions for loans, “Don’t be afraid to ask about borrowing. You never know if you don’t ask,” Shewchuk recommends. One of the more unusual objects that the Institute sought for this exhibition was Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton’s wedding rings from the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University. Shewchuk approached the ask with the heart of the story she wanted to tell with this exhibition. “For this wedding ring to travel back to Albany, to the city where he [Alexander Hamilton] put it on her hand would be an incredibly moving part for this exhibition and the story… and that was the story I pitched.” Her approach worked and the wedding ring was allowed to be part of this exhibition for three months. For Shewchuk, the confirmation that Elizabeth’s wedding ring would be part of the exhibition was a special moment in the entire process. “When you get the email that says, ‘yes, we’ll lend’ [from Columbia University] you start to cry...and when the courier asked when was the last time that this ring was in the same room with Elizabeth’s portrait, you get chills.”

Elizabeth (Eliza) Hamilton portrait hangs on the wall to the right of her husband, Alexander Hamilton with her wedding ring displayed between.

Coming Together

“The hardest part is the logistics, is getting things here, handling the special requirements that can vary from museum to museum, and trying to time it,” Shewchuk shared. The last item for the exhibition arrived just two days before opening. With all the objects coming together to tell the Schuyler sisters’ stories, items loaned from nearby Schuyler Mansion provided the most poetic completion for this exhibition. Household and personal items that might have been used by the sisters including chairs, a tea set, and clothing. Schuyler Mansion is the site where the family lived, and where Alexander Hamilton proposed to Elizabeth in the parlor that helped to launch these sisters and their lives into public intrigue with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway phenomenon “Hamilton.”. It might be these objects that Schuyler Mansion loaned to the Albany Institute that are the most moving. Perhaps the last time that these objects we all together with the people who used them was at the mansion and now these objects are all back in Albany and under one roof, telling this story.

You can visit “The Schuyler Sisters and Their Circle” at the Albany Institute of History & Art is on until December 29, 2019. The Institute is open Wednesday 10 AM - 5 PM, Thursday 10 AM - 8 PM, Friday and Saturday 10 AM - 5 PM, and Sunday Noon - 5 PM.